While Canada holds Dr. Norman Bethune (Class of 1916) in high regard for his medical ingenuity, China idolizes him

The reason why Dr. Bethune is less celebrated in his home country has more to do with his belief in communism than his lack of accomplishments as a military surgeon in China. For decades, Canadians couldn’t view a physician who risked his life to help communists in China as worthy of respect.

But in 1970, when Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau forged diplomatic relations with China and named Bethune “a Canadian of national historic significance,” a sort of “Bethunemania” erupted. Filmmakers, poets, and writers delved into his life story, and a Toronto high school was named in his honour. Still, many Canadians couldn’t forgive him for being a communist.

Early days

Born in Gravenhurst, Ontario, in 1890, Henry Norman Bethune had a boyhood hero: his grandfather, Dr. Norman Bethune, who began his medical education at King’s College, which later became the University of Toronto. Young Henry was impressed that during the Crimean War, his granddad had been a military surgeon. At the age of eight, Henry hung his grandfather’s nameplate on his bedroom door and insisted he was no longer Henry, but Norman.

As a boy, he seemed to look for trouble and was often at odds with his father, a Presbyterian minister. Although Norman participated in daily Bible study while growing up, he eventually claimed to be an atheist.

Becoming a physician

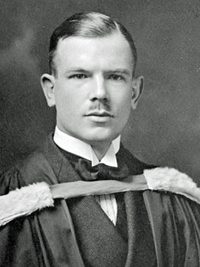

In 1912, Bethune started U of T’s medical program. But just as he was about to enter his third year, Great Britain declared war on Germany. Bethune was among the first Canadians to enlist, eager to serve king and country but perhaps most of all, to quench his adventurous spirit.

In 1912, Bethune started U of T’s medical program. But just as he was about to enter his third year, Great Britain declared war on Germany. Bethune was among the first Canadians to enlist, eager to serve king and country but perhaps most of all, to quench his adventurous spirit.

At the beginning of the First World War, Bethune joined the army medical corps and was posted in France as a stretcher-bearer. Six months later at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium, shrapnel severely injured his leg.

After recovering, he was disappointed not to be sent back to France but told to complete his medical training. After an accelerated program at U of T, Bethune graduated in December 1916 alongside Frederick Banting.

Bethune started his medical career by doing a locum in Stratford, Ontario. In spring 1917, he returned to Toronto where, while walking down the street, a woman pinned a white feather on his lapel. This symbol of cowardice made him question why he was strolling around the city, enjoying the spring breeze, when Canadians were dying overseas in trenches.

That fall, he enlisted in the navy, remaining on the H.M.S. Pegasus until the war ended in November 1918.

Changing direction

The following year, Bethune interned in pediatrics in Edinburgh and London, England. He also became fascinated with surgery, starting his surgical career at Toronto General Hospital in 1921.

Then in 1928, Bethune joined thoracic surgical pioneer Dr. Edward Archibald, surgeon-in-chief at Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. There, Bethune developed or modified 12 thoracic surgery instruments including the Bethune Rib Shears, which he modelled after the leather-cutting scissors at the United Shoe Machinery Company. Shears after the Bethune Rib Shears are still in use today.

Bethune wasn’t just creative. He was restless, temperamental, and prone to spewing unpopular beliefs about the medical system. After five years, Archibald fired Bethune. But soon, Bethune was appointed the Chief of Thoracic Surgery at a hospital just north of Montreal. Three years later, he left the position having trained two thoracic surgeons to take his place.

Ahead of his time

While in Montreal, Bethune became acutely aware of the socio-economic aspects of health. He opened a free-of-charge clinic on Saturday mornings for those who couldn’t afford care. On the radio, he provided education on how to prevent tuberculosis.

Bethune was critical of his fellow physicians. In a speech he said, “We set ourselves in practice, all smug and satisfied, like tailor shops. We patch an arm, a leg, the way a tailor patches an old coat. We’re not practising medicine, really, we’re carrying on a cash-and-carry trade.”

In a presentation to those eager for reform, he took his ideas a step further: “Let us take the profit, the private economic profit, out of medicine, and purify our profession of rapacious individualism. Let us make it disgraceful to enrich ourselves at the expense of the miseries of our fellow men.”

In the 1930s, Bethune began pressuring the government to make radical reforms and provide free health care to all. He demanded that doctors be placed on salary. In 1935, discouraged by the lack of change, Bethune joined the Canadian Communist Party.

His most renowned invention

In 1936 the Spanish Civil War broke out, and Bethune was soon in Madrid to help fight fascism. His years as a stretcher-bearer in the First World War made him aware that most wounded soldiers needed to receive blood soon after they fell.

The idea of a mobile blood bank wasn’t new, but no one could summon the nerve to pursue it. Bethune, a risk-taker since childhood, dared to try.

At the time, transfusions were made directly from one person to another. The idea of creating a blood bank and storing blood in bottles was revolutionary.

Every blood donor needed to be tested for malaria and syphilis, which were endemic in Spain. But with thousands of young men in immediate need of blood, Bethune and his colleagues decided that a wounded soldier would want to live – even if he acquired syphilis. Later, the soldier could be treated for the disease. To meet the urgent need, the team decided to test only for blood type.

Over the radio, Bethune asked for blood donors. The next morning, a long line of volunteers snaked around several blocks.

To take the blood onto the battlefield, Bethune devised a vehicle that included a refrigerator, sterilizing unit, and equipment for giving blood transfusions.

The service grew quickly. Soon, the vehicles were serving on a frontline that measured 100 kilometres. The mobile blood bank was dubbed one of the greatest innovations in military medicine, but Bethune joked that it was just a “glorified milk delivery service.”

Going to the wounded

Bethune wanted to support the Chinese Communist Party during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In January 1938, he arrived in Yenan where he met Chairman Mao, who had heard of Bethune’s heroics in Spain. Mao urged him to create travelling blood banks and encouraged Bethune’s latest idea: a mobile surgical unit.

To prepare for surgery on the battlefield, Bethune designed wooden containers that fit on the backs of three mules. The boxes contained surgical instruments that Bethune designed, and that local carpenters and blacksmiths made. They also held a collapsible operating table, antiseptics, 500 dressings, and 500 prescription drugs.

In China, Bethune courageously performed emergency surgery in the midst of battle, treating casualties from both sides.

With about 2,300 wounded soldiers in hospitals, Bethune urgently needed more health care workers. Instead of despairing, he trained young village men in anatomy, physiology, and how to treat minor wounds. Calling the men “barefoot doctors,” he graduated them in one year.

Bethune worked constantly. In his diary he wrote, “It is true I am tired but I don’t think I have been so happy for a long time. I am content. I am doing what I want to do.”

Final days

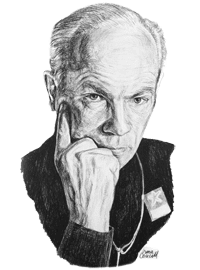

Portrait by Irma Coucill, Canadian Medical Hall of Fame

While operating on a wounded soldier, Bethune accidentally cut his finger on an osteotome. He bandaged it and kept right on working. A few days later, while performing surgery on a soldier’s infected brain, the micro-organisms seeped through his still-open wound. Within two weeks, he was feverish and couldn’t get out of bed. Refusing to have his arm amputated, Bethune, at age 49, died of septicemia on November 12, 1939.

A month after his death, Chairman Mao wrote a eulogy for Bethune that became mandatory for all Chinese schoolchildren to memorize. The eulogy includes this passage:

“We must all learn the spirit of absolute selflessness from him. With this spirit everyone can be very useful to the people. A man’s ability may be great or small, but if he has this spirit, he is already noble-minded and pure.”

Photo at top of page: On May 30, 2014, a life-sized statue of Dr. Norman Bethune was unveiled outside U of T’s Medical Sciences Building near Queen’s Park Crescent. The bronze statue, designed by famed Canadian artist David Pellettier, features Bethune in traditional Chinese clothes. The statue was made possible through a donation from philanthropists Zhang Bin and Niu Gensheng in China. To watch Pellettier create the statue, visit here.