Dr. Bill Mustard had a brilliant surgical career in both orthopedics and cardiology.

When William (Bill) Mustard graduated from U of T Medicine in 1937, he was the youngest in his class. Only 22 years old, he was thought to be the youngest physician in Canada.

When William (Bill) Mustard graduated from U of T Medicine in 1937, he was the youngest in his class. Only 22 years old, he was thought to be the youngest physician in Canada.

While still a fledgling doctor, Dr. Mustard began pioneering groundbreaking surgeries. He contrived an operation for use on the battlefield that could save a soldier’s injured leg from amputation. He developed a muscle transfer operation for polio victims that restored the children’s ability to walk. Later, he invented a way to reconnect transposed blood vessels in the heart, an operation that saved the lives of thousands of children around the world.

But when he was 17, old enough to register at U of T Medicine, he almost didn’t. Emotional and soft-hearted, he was intimidated by the university’s grand size and sheepish about applying. His older brother Donald Mustard, who was in the Class of 3T4, took Bill under his wing and helped him sign up for medicine.

At U of T, Bill Mustard concentrated on sports, not his studies. He might have flunked out were it not for a classmate who took meticulous notes for him while Mustard competed on gymnastics, swimming, diving, and football teams, or simply fooled around.

When Mustard did attend class, he was the class clown. For Daffydil, he wrote and performed risqué skits that brought the house down.

Regarding the practice of medicine, though, he was indifferent.]

About face

After graduating and spending a year in a rotating internship at Toronto General Hospital and a year interning at the Hospital for Sick Children, Bill found his calling: surgery. But as he was perfecting his skills in Toronto and New York, the Second World War was escalating. In 1941, he interrupted his training to join the Royal Canadian Medical Corps.

In the Corps, Mustard, then 26 years old, pioneered an operation that eliminated the need to amputate a limb with severe artery damage. At a casualty clearing station in Europe, Mustard bridged a lacerated artery in the leg with a glass tube and managed the patient with heparin. A few days later, he replaced the tube with a vein graft. While he had minimal success with the operation, American surgeons went on to perfect it during the Korean War.

After returning from war, Mustard, still in uniform, walked into SickKids where he was welcomed, appointed Chief Resident, and continued his training. Soon after, Mustard discovered he had a second calling: teaching.

“We all admired Bill Mustard when we were students and later as residents,” recalls Dr. George Trusler (Class of 4T9). “He was brilliant, a skilled surgeon, and refreshingly humorous.”

Mustard loved to make people laugh and to surprise them. At the university that once terrified him, he would stand on his head to get the attention of postgraduate students. His undergraduate lectures were so full of fun that at the end of class, the students would give him a standing ovation.

More than just funny, Mustard was ingenious. For children with hips paralyzed by polio, Mustard developed an operation for moving the iliopsoas muscle from the front to the back of the hip to stabilize it.

The iliopsoas transfer, dubbed the “Mustard Procedure,” brought him international fame and enabled hundreds of children with polio to not only walk again, but to run and jump once more.

Dr. Robert Salter (Class of 4T7), who trained under Mustard and became a renowned orthopedic surgeon, called the operation “by far the best muscle transfer ever devised for the hip.”

Mustard found great joy in seeing children who had limped into the hospital on crutches walk out unaided. And although not every orthopedic surgery produced perfect results, the children seldom died. But increasingly, he was doing heart surgeries, which had a high mortality rate.

In 1957, Chief of Surgery Dr. Albert Farmer (Class of 2T7) wanted to introduce surgical specialties. Salter was the obvious choice for Chief of Orthopedic Surgery, and Farmer made Mustard the Chief of Cardiovascular Surgery.

Life on a rollercoaster

The congenital heart defect field was filled with ups and downs. Mustard was ecstatic when a heart operation saved a child, devastated when a child died. Sleepless nights followed sleepless nights. He developed two medical conditions that may have been caused by the enormous stress he was under. In his 40s, Mustard had a heart attack and nearly died. Later, he required two blood transfusions for a bleeding ulcer that may have been caused by the enormous stress he was under.

In the surgical theatre, though, Mustard was buoyed by those around him. There were always eager residents, and Mustard trained more than 60 cardiac surgeons. The anesthesiologists he worked with told good jokes. And, increasingly, skilled surgeons were at his side.

“I joined the staff of the Hospital for Sick Children in July 1958 to do general children’s surgery but also cardiovascular surgery to support Bill who was otherwise on his own,” recalls Trusler, who became partners with Mustard, sharing both financial matters and patients.

“Those were exciting days,” Trusler continues. “Open-heart surgery had been going on in some centres for four or five years, but mortality was fairly high. When I started with Bill, we increased our volume to one open-heart patient per week. That represented a lot of work. There was no ICU, and we were having to learn on the job.”

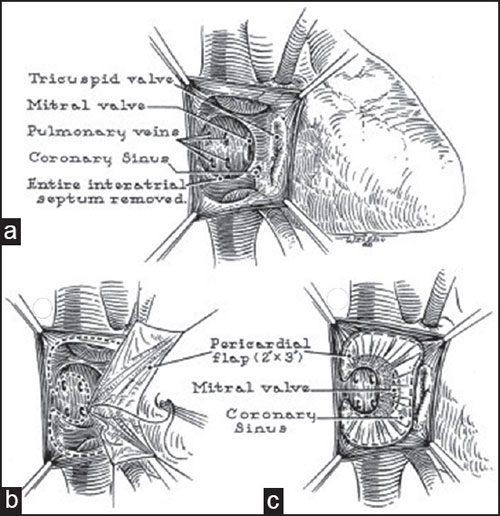

The minimal resources didn’t stunt Mustard’s creativity. He invented the atrial switch operation for patients with transposition of the aorta and pulmonary artery. The congenital heart defect caused a low blood-oxygen level, causing the infant’s lips and skin to be blue. These “blue babies” had less than a 20 per cent survival rate. But with the “Mustard Operation,” survival to adulthood shot up to 80 per cent.

Mustard operation. Pericardial baffles are used to direct vena caval blood to mitral valve and pulmonary venous blood to tricuspid valve. (a) Atrial anatomy. (b) Suturing of pericardial baffle. (c) Completed procedure (Reproduced with permission from: Mustard WT, Surgery; 1964;55:469-72.) ©Annals of Pediatric Cardiology

“Looking back now, it is amazing to me that Bill Mustard devised and performed his repair of the transposition of the great arteries as early as 1962,” says Trusler. “It was a brilliant operation at the time. Cardiac surgeons and cardiologists worldwide welcomed the operation immediately, and Bill Mustard was famous in that community. Many surgeons visited, and we were busy.”

In Mustard’s later years, his eyesight began to fade, forcing him to retire in 1976. Then in 1986, he was diagnosed with aortic valve stenosis. He declined surgery. On December 11, 1987, the internationally renowned cardiac surgeon died of a massive heart attack.

Portrait from Canadian Medical Hall of Fame

Top photo: Bill Mustard in the operating room